San Fransicko Is Incorrect About Housing Affordability and Homelessness

By Ned Resnikoff on January 24, 2022

The most influential and widely read book about homelessness to be released in the past year is undoubtedly San Fransicko: Why Progressives Ruin Cities. Amazon currently lists the book at both #1 and #4 (hardcover and Kindle editions, respectively) on its list of bestsellers in the “Urban & Regional Economics” category. Author Michael Shellenberger has been interviewed on The Joe Rogan experience, one of the most popular podcasts in the world. His book has been reviewed in the New York Times and cited in the Washington Post.

It’s a testament to the book’s popularity that I placed a library hold on it almost three months ago and was only able to pick it up last week. I felt it would be worth the wait. Given that much of San Fransicko is a direct challenge to the housing first model of addressing homelessness, it seemed worthy of serious engagement. (I should note that the book also repeatedly criticizes BHHI’s director, Margot Kushel, by name. In the interest of full disclosure, let me add that in response to an earlier post on this blog, Mr. Shellenberger accused me of lying and bullying journalists. I encourage you to read the offending post for yourself to judge whether he’s correct; I always aim for courtesy and professionalism when writing this blog or speaking to reporters, although it’s certainly possible that I sometimes miss the mark.)

I described San Fransicko as a book about homelessness, but that’s not quite right: while much of the book is dedicated to discussing the homelessness crisis in West Coast cities, its ambitions are much broader than that. There are chapters about urban crime rates and policing; substance use disorder and harm reduction; the cult leader Jim Jones; a short chapter that summarizes the entire history of psychiatry; and some rather surreal digressions into critiques of Marx and Foucault. Most of those topics are well outside my wheelhouse, so I’m going to confine this post to a discussion of something about which I do know a thing or two: the link between housing unaffordability and homelessness.

Challenging the evidence of this link is central to Shellenberger’s project in San Fransicko. Contra the expert consensus that America’s homelessness crisis is primarily fueled by stagnant incomes and out of control housing costs, Shellenberger asserts that the bigger issue is a combination of rampant substance use disorder, mental illness, and a climate of decadent moral permissiveness in liberal cities. This assertion, made early in the book, is key to nearly everything that follows.

Shellenberger’s Argument

San Fransicko’s argument against housing unaffordability as the primary driver of homelessness can be summarized as follows:

- Homelessness in West Coast cities rose during a period when homelessness nationwide was declining. Other cities, such as Chicago and the metropolitan areas of Miami and Atlanta saw significant declines even as Bay Area homelessness rose precipitously.

- Other cities with expensive housing (Shellenberger cites Palo Alto and Beverly Hills) do not have San Francisco’s homelessness problem.

- The empirical research on housing unaffordability and homelessness is less clear than housing first advocates suggest. For example, an oft-cited Zillow study has been widely misinterpreted.

- Homeless people are disproportionately likely to suffer from debilitating behavioral health problems, including substance use disorder. These conditions must have caused their homelessness.

That is roughly the order in which these claims first show up in the book. I already addressed #4 in the earlier blog post that invoked Shellenberger’s ire, so I’ll only add that it’s well known among homeless service providers that, as one group of researchers put it, “the association between homelessness and drug use is bidirectional.” Preexisting substance use issues or behavioral disorders can certainly make it harder to retain stable housing; conversely, bouts of homelessness can be so traumatizing that they have ruinous effects on one’s mental health or can lead one to self-medicate. Shellenberger takes a shortcut to a tidy causal inference when the reality is far messier.

But the broader issue is that this messy reality is taking place against a backdrop of stratospheric rents and home prices. Low-income people—many of whom have preexisting behavioral health struggles—get very little margin for error if they hope to remain housed. That is where the other elements of Shellenberger’s argument come in.

Revisiting the Zillow Study

Since I have repeatedly cited the aforementioned Zillow study in the past, let’s take a closer look at it. Shellenberger says the study’s findings are “more nuanced” than others (including myself) have suggested. According to San Fransicko’s gloss on the study: “Homelessness and affordability are correlated only in the context of certain ‘local policy efforts [and] social attitudes.’”

That is certainly not how I remembered the study’s conclusion, so I revisited the paragraph Shellenberger is referencing (emphasis mine):

Because homelessness often appears to involve a jumble of factors that are difficult to tease apart, it can be useful to quantify some of the main factors. Rent affordability is one, as is the poverty rate. The model for this research also produced a baseline estimate for the homeless population in each market – the population that the model indicates might be homeless regardless of housing costs and the poverty rate. It’s an informed, but hypothetical, statistical starting point in relation to the market’s peers before considering other factors. To that baseline, the model adds the effect of the poverty rate and rent affordability, as well as unknown and unobserved “latent” factors that could include everything from local policy efforts to social attitudes toward homelessness to the weather in a given locale. Each force can act as a headwind to push homelessness higher or a tailwind that pulls it down.

Shellenberger is misreading the bolded sentence. The study’s authors are not saying that the correlation between rent affordability and homelessness disappears when one controls for policy efforts and social attitudes; quite the opposite, in fact. Their model included a variable meant to simulate the effect of these factors and found that differences in rent affordability still explained a significant amount of the variation in local homelessness rates. Public policy and social norms do matter; if they didn’t, then there would be no reason for me to work on homelessness policy and write about it for a general audience. But these factors in no way eclipse the role of housing unaffordability in the Zillow study.

By the way, it’s generally a good idea for journalists who are confused about the findings of a report to contact the authors directly and confirm whether their interpretation makes sense. For example, I reached out to one of the economists who worked on the Zillow study and confirmed that my interpretation of the above paragraph, not Shellenberger’s, was the correct one.

The Zillow Study Is Not Alone

It is strange that Shellenberger devotes his attention exclusively to the Zillow study. A broader literature review would have uncovered a lot of corroborating research on the relationship between housing unaffordability and homelessness.

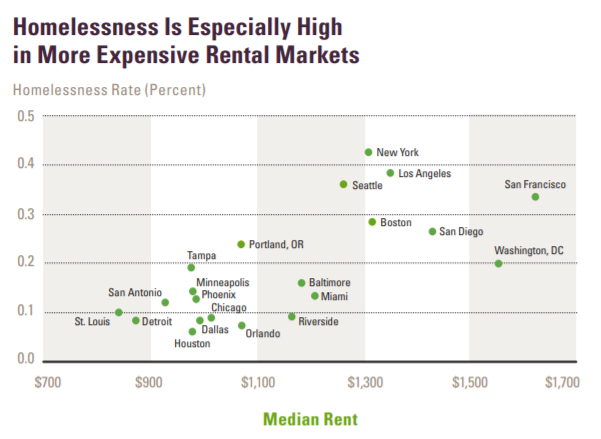

For example, here is a chart from a 2017 report of Harvard’s Joint Center for Housing Studies showing the correlation between rates of homelessness and median rents:

Similarly, the below tweet includes charts from an upcoming book with the appropriate and pithy title, Homelessness is a Housing Problem:

We focus on cities, not individual people. And when you take a metropolitan lens, rents and vacancy rates arise as some of the only credible explanations for regional variation in rates of homelessness. Not poverty; not the generosity of public assistance; not drug use. pic.twitter.com/BPEahIyw3V

— Clayton Aldern (@compatibilism) November 17, 2021

The Zillow study is a valuable contribution to the body of economic work on homelessness, but it is neither the first nor the only study to find a significant relationship between homelessness rates and housing unaffordability. One wishes Shellenberger had dived a little deeper into the literature before writing a book purporting to rebut it.

Dubious Comparisons

In the same chapter where Shellenberger misreads the Zillow study, he writes the following [emphasis his]:

Other cities, including Chicago, Houston, and the Greater Miami area, saw typical rents increase 24 percent, 32 percent, and 35 percent and the number of homeless decline 20 percent, 57 percent, and 9 percent, between 2011 and 2019, which are the years covered by the Zillow study (2011-2017), plus 2018 and 2019. In Nashville, the number of chronically homeless fell 54 percent in the same period.

Elsewhere, he notes: “Homelessness nationwide declined from 763,000 to 568,000 between 2005 and 2020. In the same fifteen-year period, the homeless populations of Chicago, Greater Miami, and Greater Atlanta declined 19 percent, 32 percent, and 43 percent respectively.” His point is that increases in homelessness among the uber-liberal cities of the West Coast cannot be fully explained by housing costs or broader national trends.

A few thoughts about this line of argument:

- I found it odd that Shellenberger choose 2005 and 2020 as his two references years for looking at Chicago and the metropolitan areas of Atlanta and Miami. Between 2007 and 2009, the United States experienced the greatest collapse in housing prices of at least the past 60 years. He is ignoring a massive exogenous shock in between the two points he examines.

- With the exception of the Miami-Fort Lauderdale metropolitan area, all of the other cities Shellenberger mentions as counterpoints to the West Coast experience score fairly well on Zillow’s rent affordability index. So even though average rents in those cities may have been rising in absolute terms, they fall below the threshold where Zillow’s model predicts they would be associated with rapid increases in homelessness.

- Another odd thing about Shellenberger’s use of counterexamples is that all these cities have housing first-style programs operating in them. Here is an essay about Houston’s.

- The reason for large studies that look at every major metropolitan area in the United States is that individual cities will always deviate from what any model predicts, sometimes by a significant degree. For that reason, cherry-picking a handful of cities and looking at two arbitrary points in time for each is not particularly useful.

- It’s worth noting that the Zillow study specifically cites Houston as an example of a city that deviates from what the researchers’ model would predict in interesting ways. Again, no one is denying that local conditions and public policy play a role; the question these studies are attempting to answer is about the overall significance of housing costs, across all cities.

Lastly, Shellenberger writes: “Palo Alto and Beverly Hills have mild climates and expensive housing but don’t have San Francisco’s homeless problem.” That is, to put it mildly, a wild comparison. San Francisco is the urban core of a major metropolitan area; Beverly Hills is an affluent community of fewer than 35,000 people on the western edge of its area’s actual urban core, the city of Los Angeles. Similarly, Palo Alto is a wealthy South Bay suburb; it is bordered by the significantly poorer and more racially diverse city of East Palo Alto.

A more reasonable (though still flawed) comparison would be between San Francisco, the Los Angeles metropolitan area, and Santa Clara County, which includes both Palo Alto and the major urban center of San Jose. Unfortunately, this comparison would not do much to help Shellenberger’s argument, as Santa Clara County and Los Angeles both have significant homeless populations.

Or Maybe Housing Affordability Matters After All

Somewhat bizarrely, Shellenberger seems to abandon his commitment to framing homelessness as anything but a housing affordability issue deeper into San Fransicko. In a late chapter, after providing some back-of-the-envelope estimates of what it would cost to house everyone who is currently homeless in California, he asks: “But what can be done to prevent the homeless population from simply replenishing itself?”

The answer, as it turns out, is building more housing. Shellenberger goes on to note that “California has the second-highest cost of living in the country,” largely because of the state’s severe housing shortage and the resulting out of control housing costs. This is all true, although the implied connection between homelessness prevention and building more housing is in significant tension with what Shellenberger argues in earlier chapters.

The book never resolves that tension. Perhaps that is because any attempt to do so would lead to the tacit admission that one of its core premises—that the homelessness crisis is first and foremost a substance use and mental illness crisis—is plainly wrong.