How The Atlantic's Big Piece on Meth and Homelessness Gets It Wrong

By Ned Resnikoff on November 15, 2021

Via Michael Hobbes’s Twitter account, I see The Atlantic has published a lengthy article on a new strain of crystal meth that is said to be “worsening America’s homelessness problem.” The Atlantic piece is about a month old at this point, but I thought it would nonetheless be worth examining here. Primarily that’s because it serves as a good showcase for several common misconceptions about homelessness.

The author of the Atlantic piece, Sam Quinones, is a veteran journalist and the author of two recent books about the opioid epidemic. (His Atlantic article was adapted from the more recent of the two.) I’ve been reliably informed that his reporting on this subject is terrific, and I have no reason to doubt that assessment. Indeed, Quinones is persuasive and compelling where his Atlantic piece details the rise of the P2P-based meth over its ephedrine-based competitor, and the havoc the more potent P2P-based form can wreak in people’s lives. It is when he turns his attention to the homelessness crisis that his story begins to fall apart.

Quinones argues that P2P meth is fueling an increase in homelessness. He cites the following evidence to support this claim:

- Two personal narratives concerning Southern California residents whose meth addiction contributed to their descents into homelessness.

- Anecdotal reports from a beat cop and a physician who both note a rise in severe mental illness among homeless Skid Row residents and attribute this to increased meth use.

- The assessment of Los Angeles Superior Court Judge Craig Mitchell that, in Quinone’s words, “the most visible homelessness—people sleeping on sidewalks, or in the tents that now crowd many of the city’s neighborhoods—was clearly due to the new meth.”

The piece includes a few gestures toward other possible causes of homelessness: “homelessness, of course, has many roots,” Quinones concedes. But, citing Mitchell, he dismisses housing costs as “very high but hardly relevant to people rendered psychotic and unemployable by methamphetamine.” Policymakers focus on housing costs and ignore substance use disorder (SUD) among the unhoused, he suggests, out of a soft-hearted desire to avoid stigmatizing unhoused people.

The story Quinones is telling about meth and homelessness can be broken into two parts. The first is a causal narrative that says widespread meth use is causing homelessness to increase in the aggregate. The second part is an argument that unhoused people with SUD face more barriers to getting out of homelessness. There is some truth to part two of Quinones’s account, but part one is plainly false.

What’s Really Driving Homelessness

Here it is worth distinguishing between the precipitants of homelessness and the main drivers of homelessness. Precipitants of homelessness are particular and non-generalizable; they are the set of individual circumstances that cause a particular person to become homeless. SUD is a common precipitant. So is fleeing domestic violence, becoming unemployed, or getting hit with unexpected medical bills. The precipitants of homelessness can be some combination of structural factors, personal mistakes, and plain bad luck. They help explain why a particular person became homeless, but they aren’t necessarily drivers; they can’t tell us why the overall rate of homelessness is so much higher in California than it is in other states.

While SUD can be a precipitant of homelessness, it does not drive overall rates of homelessness. If it did, we would expect West Virginia—which leads the nation in drug overdose deaths—to have more homelessness on a per capita basis than California. But West Virginia actually has one of the lowest rates of homelessness in the country. Why? Because housing in West Virginia is cheap. According to the National Low Income Housing Coalition, the standard fair market monthly rent for a two bedroom unit was $771 per month in West Virginia and $2,030 per month in California. At those prices, someone who is struggling—whether due to SUD or for some other reason—may be able to find housing in the former state when they would have become homeless in the latter.

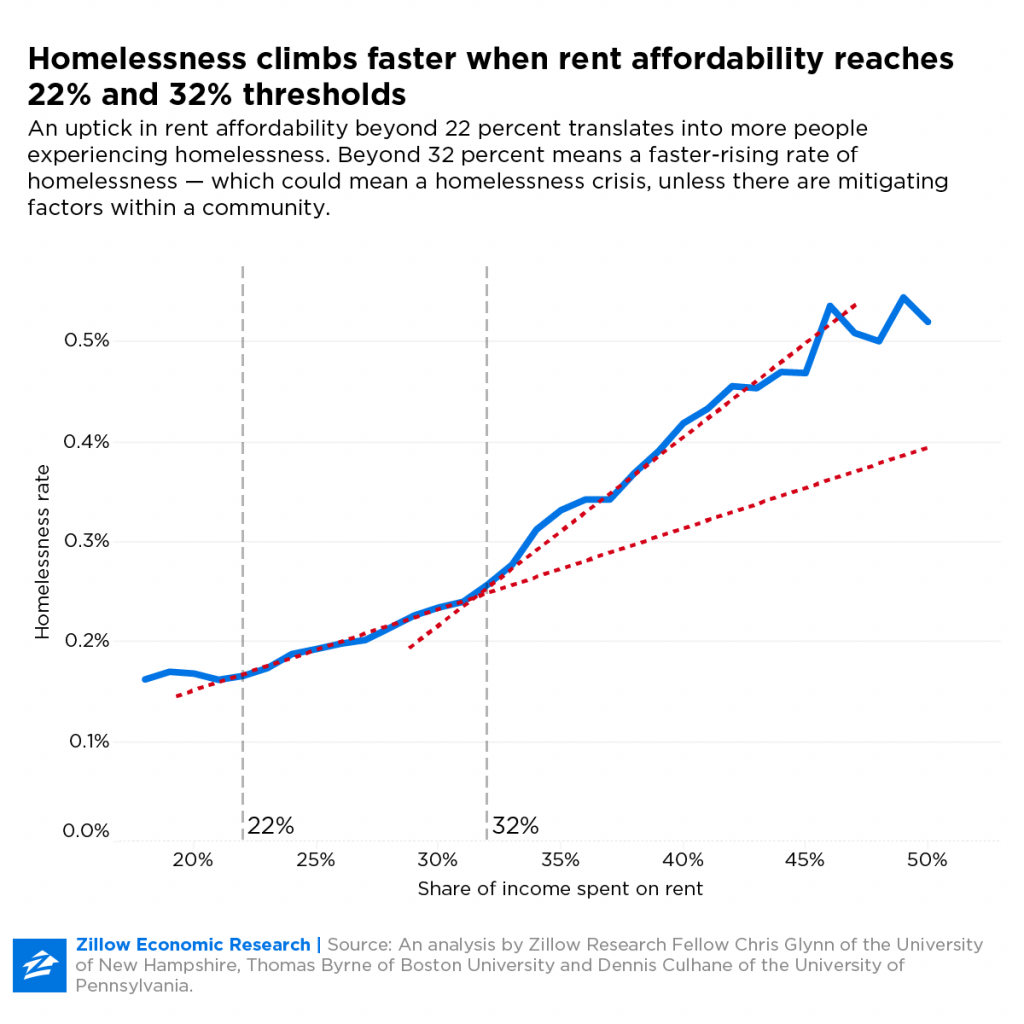

Which brings us to the actual main driver of homelessness: housing unaffordability. The below graphic from a report by Zillow’s economics research arm may not be as gripping as Quinones’s prose, but it tells a more accurate story about why we’ve seen such dramatic increases in homelessness over the past several years.

Indeed, between 2012 and 2020—the time over which Los Angeles’s homeless population more than doubled in large part, Quinones argues, because of widespread meth usage—the city’s housing prices also nearly doubled.

SUD, Homelessness, and Recovery

So much for Quinones’s causal story about the link between meth use and homelessness. The second part of his argument—that SUD can pose a significant barrier to ending homelessness for many unhoused people—fares better, though it is incomplete. While we don’t know exactly how many unhoused people struggle with SUD, it seems to afflict a particularly high share of the unsheltered population: a 2019 California Policy Lab report estimated that roughly half of unsheltered people in Los Angeles have an SUD, although the report’s authors acknowledged significant limitations inherent in the dataset they were using. On top of those methodological challenges, is unclear how many of those people developed SUD before becoming unsheltered, and how many did after. In either case, it is undeniable that SUD can make it a lot harder to emerge out of homelessness, even with help. It may even be true that those with severe P2P meth dependencies are among the hardest people to help.

But it is simply wrong to suggest—as Quinones does, again paraphrasing Mitchell—that “nobody wants to talk about it.” In fact, there has been a ton of research on how to end homelessness for people with severe SUD. I highlighted some of that research in an earlier blog post describing the permanent supportive housing (PSH) model. As I summarized it then, PSH “prioritizes moving unhoused people with particularly high needs into permanent housing while also offering them a variety of optional services.”

I wrote:

My own favorite study of the PSH model—the study I find myself returning to again and again—comes from here at BHHI. [BHHI Director Margot Kushel], fellow BHHI faculty member Maria Raven, MD, and Matthew Niedzwiecki, PhD, conducted a randomized control trial of a PSH intervention offered in Santa Clara County on a Housing First basis. (For those who don’t consume much social science research: Randomized control trials are just about the closest you can get to replicating ideal laboratory conditions when studying a policy intervention out in the field.) The target population for this intervention was people with extremely high needs; as the researchers noted in their writeup of the study for Health Services Review, “Participants averaged five hospitalizations, 20 visits to the emergency department, five to psychiatric emergency services, and three to jail in the two years prior to being enrolled.”

In other words, this Housing First-aligned treatment was specifically for the hardest-to-treat members of Santa Clara’s unhoused community. The results of the intervention were extraordinary: 86% of those who received the treatment were successfully housed and remained housed for the vast majority of the follow-up period (which averaged around three years). Similarly, there was a sharp drop in utilization of emergency psychiatric services among the treatment group, corresponding to a rise in scheduled mental health visits.

Not only does Housing First work, but the evidence shows that it can work for even the highest need population of people experiencing homelessness. The 86% success rate cited in the Health Services Review article, while impressive, actually understates the intervention’s effectiveness. When BHHI researchers revisited Santa Clara for additional data, they found that more than 90% of participants had been housed and remained housed over the long term.

Rather than refusing to talk about the prevalence of SUD in California’s unhoused population, researchers have been developing effective interventions; and policymakers and practitioners have been working to implement them.

None of this policy development has been happening in secret. In fact, a lot of interesting work has been happening in Los Angeles, where Quinones did much of his reporting. I already mentioned the Los Angeles branch of California Policy Lab; that is just one organization amid a broader ecosystem of Los Angeles-based research institutes and service providers that includes the Price Center for Social Innovation, the St. Joseph Center, and, of course, the Los Angeles Homeless Services Authority. It is a shame the Atlantic piece does not include any of their voices. Perhaps their voices could have clarified that the homelessness crisis is being driven first and foremost by housing unaffordability—and that there is no solution to homelessness without housing.