A common theme of this blog is that rising housing costs—or, more precisely, housing unaffordability—go most of the way toward explaining mass homelessness in the United States generally and California in particular. But that straightforward diagnosis opens up additional questions of a thornier nature: How did housing costs get out of control in the first place? Why haven’t incomes kept pace with rents? And why has it proven so difficult for policymakers to implement even modest efforts to increase housing supply and rein in costs?

Furthermore, the modern era of homelessness began more than four decades ago; how did it start? Why didn’t we do something back then? Why aren’t we doing enough now? And why has rising housing unaffordability become a global phenomenon, with local variants in Europe, Latin America, and East Asia?

These are questions that can’t be answered using the tools of policy analysis. Instead, they take us into the realm of political economy. To answer these questions, we need to build a functional model of the system that has suppressed wage growth and inflated home prices over the past half century. We need to understand how this model developed and why it has proven so durable; why, in other words, it has commanded enough political support to remain largely intact even as it has produced widespread immiseration in American cities (and beyond).

I spent a chunk of the holiday season reading a book that grapples with these questions. I summarize some of its key points below, with a particular emphasis on what this all means for our efforts to prevent and end homelessness.

Wage Stagnation, Asset Inflation

The Asset Economy, written by the Australia-based social theorists Lisa Adkins, Melinda Cooper and Martijn Konings, argues that the major economies of the Anglophone world (those of the United States, the United Kingdom, and Australia) underwent a significant shift in the second half of the 20th century. Due to that shift, in their words, “[t]he key element shaping inequality is no longer the employment relationship, but rather whether one is able to buy assets that appreciate at a faster rate than both inflation and wages.”

Their argument is rather technical, but it’s worth trying to gloss some key points. Adkins, Cooper and Konings fix the roots of the modern economic order in the immediate hangover from the post-war boom of the 1950s and 60s. The post-war moment was a period of relative economic equality, driven by a growing middle class that was in turn buoyed by rising wages, government social policy, a muscular labor movement, and rapid economic growth. This expansionary phase came to a stop in the 1970s, when the Anglophone world entered a period characterized by consumer price inflation. Because wages during that era still largely kept pace with rising prices, the biggest losers from inflation were “those whose wealth was invested in financial assets such as stocks, bonds, or Treasury bills and whose income derived primarily from interests, dividends, rents and capital gains.” Inflation devalued these assets.

Policymakers responded with a variety of instruments, which the book describes in detail. I won’t do that here. Instead, I’ll skip to the ultimate consequence, which was to slow down growth in consumer prices and wages while juicing asset values. As this was going on, policymakers tried to offer new opportunities for middle- and working-class households to reap the benefits of asset inflation. As Adkins, Cooper and Konings write, “governments encouraged people to participate in the asset economy to compensate for their losses on labor income with investment income.” For the vast majority of households, the most direct path to a major stake in the asset economy was through homeownership.

The New Class System

Adkins, Cooper and Konings write that the transition to an asset-based economy—and in particular the push to get as many people as possible to participate in this economy by purchasing their own homes—fundamentally transformed the class system of the Anglophone world. “The key element shaping inequality is no longer the employment relationship, but rather whether one is able to buy assets that appreciate at a faster rate than both inflation and wages,” they write.

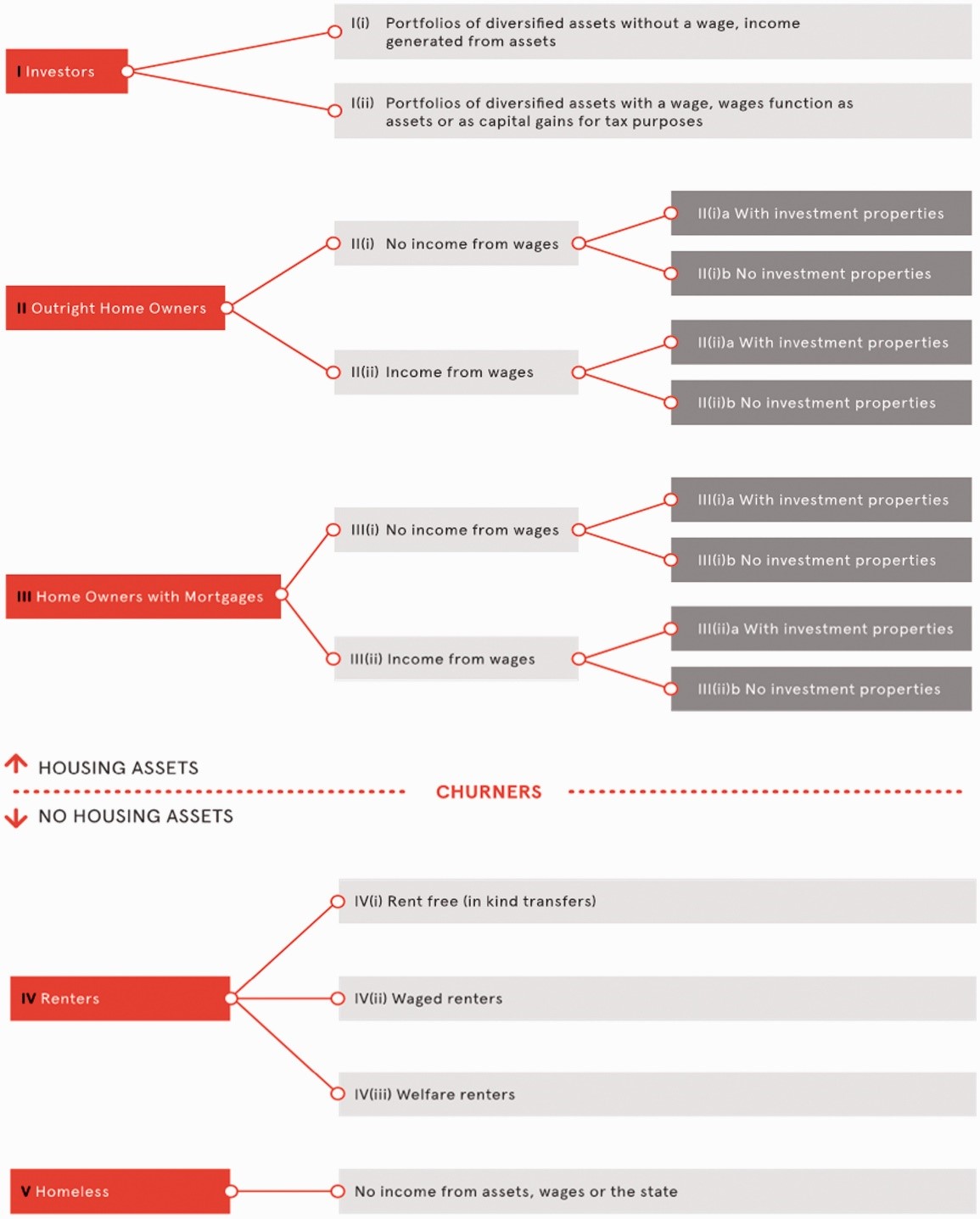

They even sketch out a rough schematic of this new class system, drawing on some of their earlier scholarship. A standard employment-based model of the class system might look something like this: Rentiers (people living off their investments) at the top, followed by the white-collar managerial class, then salaried workers, and so on. Here is how Adkins, Cooper and Konings render their model:

There are a few things I would quibble with here. In particular, it is not the case that people who are homeless never have income; they just don’t have enough of it to rent or buy housing. Similarly, many people hover indefinitely at an intermediate state between group IV and group V, either because they are only intermittently homeless or because they live in substandard housing conditions.

Because it is focused on the asset economy as a transnational phenomenon, this schema also elides a fundamental characteristic of the class system in the United States: how asset ownership maps onto racial hierarchies. Prior to the 1970s, Black and brown Americans were systematically shut out of homeownership in “white” areas (including areas that had previously been integrated) through a combination of legal restrictions and informal coercion. While overtly racist prohibitions on Black and brown homeownership no longer have the force of law behind them, de facto housing discrimination persists. And the de jure legal regime of explicit segregation has been replaced by what the scholar Keeanga-Yamahtta Taylor describes as a system of “predatory inclusion,” under which “African American homebuyers were granted access to conventional real estate practices and mortgage financing, but on more expensive and comparatively unequal terms.” As a result, the gap between Black and white rates of homeownership is actually wider now than it was in 1960. Similarly, as I have pointed out many times in the past, the Black share of the homeless population in California exceeds the white share to a staggering degree.

Those caveats aside, I think this schema represents an extremely useful way to think about class relations in the United States and beyond. I discuss some of the implications of Adkins, Cooper and Konings’ theory in the following section.

Implications

A few things make the Adkins, Cooper and Konings analysis useful. In particular:

It helps to explain why home price inflation is an international crisis. Although The Asset Economy focuses on policy developments in the Anglophone world, other nations have enacted similar policy regimes. Perhaps more importantly, the policy decisions made in wealthy countries such as Australia, the United Kingdom, and—especially—the United States have spillover effects powerful enough to influence the world economy.

It resolves some cognitive dissonance around class. Intuitively, it seems that people who have similar jobs and educational backgrounds, and earn roughly equivalent incomes should belong to the same economic class. But we all know from personal observation that this isn’t the case. The Asset Economy explains the existence of “deep chasms of inequality between classes of people who earn the same wages but are differentiated by their status as homeowners or renters.”

It provides a theoretical framework for understanding the modern era of American homelessness. As mentioned previously, we can fix the beginning of contemporary mass homelessness in the United States to somewhere around the late 70s or early 80s. That means its birth coincides roughly with the creation of the asset-based economy. While the book is not focused on the origins of the modern American homelessness crisis, it points to a critical underlying cause: as housing price appreciation began to outstrip income growth, many people on the lowest rung of the economic ladder were suddenly no longer able to afford even the most rudimentary housing.

It helps explain why preventing and ending homelessness is so politically challenging. Close to two-thirds of Americans reside in owner-occupied housing. In practical terms, that means a supermajority of Americans have a significant financial stake in the asset economy; for many of them, their financial health and the security of their families depends on rapid, perpetual asset appreciation. This means that many of the policy levers we could use to reduce the overall cost of housing (or even slow the growth of housing costs) would run directly counter to the economic interests of the largest and most powerful voting bloc in the asset-based class system. Furthermore, most of the people within that bloc are not part of the “one percent” by any reasonable definition; they are part of the generation that was granted easier access to the asset economy as compensation for stagnating wages.

Adkins, Cooper and Konings argue that a similar dilemma faces policymakers who want to dramatically increase social spending or raise incomes for those who cannot currently afford housing. They write:

As [then Federal Reserve chair Alan] Greenspan took pains to explain to [then President Bill] Clinton, it was simply not possible to square the tremendous “wealth effect” generated by sustained asset inflation with a program of serious public investment. As soon as bondholders got wind of any attempt on the part of government to inflate wages or welfare, they would fear a return to the dark years of the 1970s and immediately demand an “inflation premium” in the form of high interest rates. If it wanted to channel money into the public sector and run the risk of higher wages, the government would be putting a dampener on asset prices and capital gains. It was one thing or the other: high asset prices or public sector abundance.

One can see an echo of this passage in the inflation debates of the COVID-19 era.

It gives us a glimpse of one possible future. An important feature of the asset economy’s wealth distribution is that it naturally becomes more top-heavy over time. If home prices rise in perpetuity, then the barrier to homeownership becomes correspondingly higher for each passing generation. “The combination of inflated capital gains and deflated wages progressively closes the gates to newcomers, who struggle to buy their way into housing on wages alone,” write Adkins, Cooper, and Konings. Late entrants to the market—for example, young, first-time homeowners—become more reliant on intergenerational wealth transfers to afford even an initial down payment.

Thus, the rate of homeownership appears to be declining among each successive generation of Americans. If housing costs continue to inflate indefinitely, we can expect the prospect of owning a home to become increasingly closed off to all but the very wealthy. And as the price of housing generates additional upward pressure on rents, we can expect to see corresponding increases in homelessness.

What this all suggests is that while the obstacles to reversing increases in homelessness are considerable, our current trajectory is unsustainable. The asset economy is based on a fundamental contradiction: Broad-based homeownership combined with rapidly inflating housing costs. These two elements cannot coexist forever. Something is going to break.