Public policy academics Pamela Herd and Don Moynihan have an interesting brief in Health Affairs on how administrative burdens can harm the health of low-income people. (The piece was apparently published a month ago, but I only discovered it last week via Moynihan’s Substack, which I recommend.) Herd and Moynihan quite literally wrote the book on administrative burdens, so their work on the subject is always worth a look.

For those unfamiliar with the term, administrative burdens are the costs associated with trying to access public benefits or demonstrate compliance with the rules of a government program. These costs can be either direct or indirect. They may include the time and effort required to understand and fill out complicated paperwork, the hours spent in line at the DMV, or the embarrassing scrutiny of suspicious case managers. Many of these burdens are the result of deliberate policy choices: for example, a program meant to serve low-income households may require that applicants demonstrate need by disclosing all other sources of income.

Oftentimes, these burdens are just annoying. But they can also have the effect of screening out people who would otherwise be eligible for certain programs. We saw an example of this in the early days of California’s COVID-19 rental assistance program: at first, the application for rental assistance took two to three hours to complete (with the help of a streamlined application, that time was later cut down to between 30 and 40 minutes). The length and complexity of the application is probably a big part of what prevented many eligible households from initially accessing those rental assistance funds.

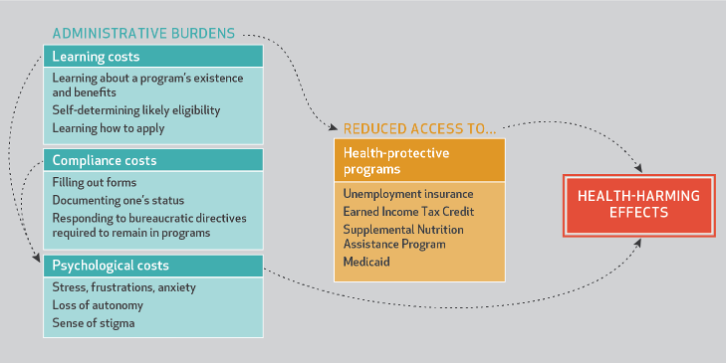

It gets worse, as the new brief from Herd and Moynihan points out. In addition to blocking access to programs that can improve the health of low-income people, administrative burdens can cause some negative health impacts of their own. This figure from the brief sums up the potential impact of administrative burdens nicely.

An especially perverse aspect of how administrative burdens operate is that their relative costs are often highest for those who are most in need of public assistance. It is harder to meet with a case manager during the day if you cannot afford childcare, or if you work in a low-wage job that doesn’t offer paid leave. Filling out extensive paperwork becomes easier with the help of a lawyer or accountant. And managing the anxiety, shame, and irritation of an involved application process can be significantly more challenging for people who already struggle with anxiety or depression.

It should come as no surprise, then, that the administrative burdens built into many public assistance programs tend to hit people experiencing homelessness or housing insecurity the hardest. Navigating these burdens may require resources that many of them lack—resources such as a stable home address, consistent Internet access, or reliable means of transportation. Furthermore, the cognitive tax of homelessness is profound. While the mental health of people experiencing homelessness is difficult to track at scale, we do know that a very high share of unhoused people experience symptoms of depression. Simply trying to survive without housing can be emotionally depleting, even before you add on the stress of a prolonged, convoluted, and (not infrequently) humiliating bureaucratic process.

Administrative burdens are likely to fall even harder on the growing population older homeless adults. A BHHI study of 350 older adults (age 50 and older) experiencing homelessness found that one-third showed signs of impairment in executive function. That is a rate of impairment, the report says, “three to four times higher than the reported prevalence in populations more than 10 years older.” People who experience these impairments find it unusually challenging to follow a set of sequenced tasks—exactly the sort of skill that is required to get over administrative hurdles.

Encampment sweeps and criminalization can make administrative burdens even more overwhelming. An unhoused Manhattanite explained how in this New York Times article on the city’s sweeps from August (emphasis mine):

According to a statement from the homeless services department, the cleanup crews do not throw away people’s belongings.

Rather, they “carefully assess” a site while noting the “number and type of possessions,” remove items to protect “valuable property” and “quality-of-life for the client,” and provide “details about how they can obtain the property.”

Max Goren, who lives in Tompkins Square Park in the East Village, has found reality to be a bit different.

“At least once a week, a sanitation truck rolls up,” Mr. Goren, 34, said in July. “If you’re not there to say, ‘Hey, that’s mine’, everything goes in the back.”

He said his possessions had been trashed three times — each time because he left them to go to a methadone clinic.

“Do I want to risk losing all of my clothes and all my bedding, or do I miss my clinic appointment?” he said.

Hindering access to public assistance is one of the ways in which criminalization and encampment sweeps actually exacerbate homelessness, rather than mitigating it.

Reducing administrative burdens and making it easier for unhoused people to access public benefits is key to helping many of them stabilize in permanent housing. But policymakers should go a step further than just streamlining paperwork. Going directly to people experiencing homelessness—literally and figuratively meeting them where they are—is often the best way to make sure they benefit from programs for which they are eligible.

Looking at COVID-19 testing and vaccinations may be instructive. A recent BHHI study of vaccine and testing acceptability among people experiencing homelessness found that “mobile outreach, which did not require [participants] to leave belongings unattended or make appointments” removed an important hurdle to receiving COVID-19 tests. Similar practices could help with enrolling more people experiencing homelessness in critical safety net programs.