Despite Progress on Protecting Renters from Eviction, More Outreach is Needed

This brief, based on our analysis of Census Pulse Data and a survey administered by BHHI and partners at UC Berkeley and UC ANR Nutrition Policy Institute, includes recommendations for how public and nonprofit entities in California can improve emergency rental assistance uptake among low-income renters. Because many survey respondents said they were not aware of the emergency rental assistance program's existence, our core recommendation is that various entities engage in public outreach to renters who are likely to be eligible for assistance.

Executive Summary

In partnership with researchers at UC Berkeley and the UC ANR Nutrition Policy Institute (NPI), the UCSF Benioff Homelessness and Housing Initiative (BHHI) collected survey data on 502 low-income parents of young children residing in California. BHHI finds that 22 percent of survey respondents who are renters have deferred rent payments since March 2020, when the COVID-19 pandemic first began to trigger large-scale shutdowns and economic dislocation in the United States. Additionally, BHHI’s analysis of Census data finds that more than 1.8 million Californians overall are still behind on rent.

While the state has provided emergency rental assistance (ERA) to many renters, only 7 percent of respondents to the UC Berkeley/NPI/BHHI survey had been paid rent relief at the time they were interviewed. Statewide, many low-income renters remain at a heightened risk of dislocation and potential homelessness when California’s eviction moratorium expires on September 30. This brief includes recommendations for how public and nonprofit entities in California can improve ERA uptake among low-income renters. Because many respondents to the UC Berkeley/NPI/BHHI survey said they were not aware of the ERA program’s existence, our core recommendation is that various entities engage in public outreach to renters who are likely to be eligible for assistance.

Background

In March 2020, during the early stages of a global economic crisis associated with the COVID-19 pandemic, the federal government instituted a temporary ban on evictions from rental properties. Around this time, Congress also authorized the distribution of $25 billion in emergency rental assistance (ERA) funds to the states. States were expected to use these funds—which were later augmented with an additional $21.55 billion—to compensate landlords and aid households that were unable to cover their rent or utilities.

Following the eviction moratorium’s expiration on July 30, 2021, the White House announced an extension until October 3. This decision was subsequently invalidated by the United States Supreme Court, though California’s statewide eviction moratorium remains in effect until September 30. Some counties and municipalities have their own moratoriums that may continue well past the state’s.

While California’s moratorium continues to offer a temporary shield against eviction for many households, only financial assistance can ensure they are not evicted for nonpayment of rent after September 30. But because the state had to create its ERA program from scratch, it was initially slow to distribute any of the funds. By July 6, 2021, California’s ERA program had approved only $137 million in payments.i

Since the program’s launch, the California Department of Housing and Community Development (HCD) has taken significant steps to speed up ERA allocation and improve access. These steps include:

- Streamlining the application for renters so it now takes only 30-40 minutes on average to complete, as opposed to 2-3 hours.

- Offering expanded translation services for applicants.

- Consolidating local ERA distribution processes and bringing them under state administration.

- Coordinating with other state departments (such as the Department of Social Services) and nonprofits to make low-income Californians aware that they might be able to receive ERA.

Additionally, in June the state enacted AB 832, which includes protections against eviction that will outlast the blanket moratorium. Under this law, landlords who wish to evict tenants over unpaid rent after September 30 must submit evidence that they first tried to determine whether the tenant was eligible for ERA.

As a result of these efforts, California has now paid out more than $525 million in ERA.ii Furthermore, the increased speed of statewide ERA allocation has increased the likelihood that California will receive additional federal funding. The United States Treasury Department has indicated that it will claw back ERA funds from low-performing states and reallocate it to states that have already obligated a significant share of their ERA.

Researchers from UC Berkeley, the UC ANR Nutrition Policy Institute (NPI), and the UCSF Benioff Homelessness and Housing Initiative (BHHI) collected survey data on a particular subgroup of lowincome Californians: parents (almost all of whom were women) of children under the age of nine. BHHI examined Census Pulse data to understand broader trends in ERA eligibility and eviction risk across the state.

Data Sources

Census Pulse Data

Since April 2020, the United States Census Bureau has been regularly collecting survey data on how Americans have been affected by the COVID-19 pandemic and the associated economic crisis. Each survey is typically conducted over the course of one or two weeks, with a gap of two days between each iteration. The “pulses” are themselves arranged into phases of the survey project, which may have larger gaps between them. These phases vary in the number of surveys they include, as well as in some survey methodology.

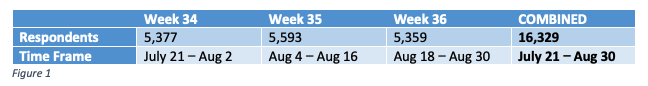

In California, a typical Pulse survey may capture approximately 5,500 respondents. To create a larger sample size, we pooled the three surveys thus far released in Phase 3.2. Figure 1 shows the number of respondents to each of these three surveys and the period over which each one was conducted.

In addition to dividing up respondents by state, the Census Pulse data further subdivides respondents into metropolitan statistical areas (MSAs). In California, the Census Pulse data can be divided into responses from four regions:

- The San Francisco-Oakland-Berkeley MSA, which includes the counties of San Francisco, Alameda, Contra Costa, Marin, and San Mateo.

- The Los Angeles-Long Beach-Irvine MSA, which includes Los Angeles County and Orange County.

- The Riverside-San Bernardino-Ontario MSA, which includes the counties of San Bernardino and Riverside.

- Other (a category which includes all California counties not listed above).

ACCESS Study Survey Data

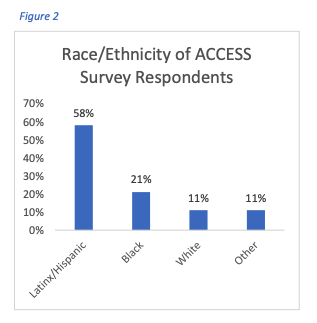

The Assessing California Communities’ Experiences with Safety net Supports (ACCESS) Study conducted by UC Berkeley, UC ANR NPI, and BHHI involved surveys of lowincome California parents with young children. Researchers asked questions about housing status, the self-reported impact of the eviction moratorium, and ERA utilization. Data collection occurred between August 2020 and May 2021, and so precedes many of the recent measures the state has taken to increase ERA uptake. The survey involved 502 participants, 94 percent of whom were female, and 98 percent of whom were housed. All survey respondents had a child under the age of nine. Figure 2 shows the racial and ethnic composition of survey respondents.

The Assessing California Communities’ Experiences with Safety net Supports (ACCESS) Study conducted by UC Berkeley, UC ANR NPI, and BHHI involved surveys of lowincome California parents with young children. Researchers asked questions about housing status, the self-reported impact of the eviction moratorium, and ERA utilization. Data collection occurred between August 2020 and May 2021, and so precedes many of the recent measures the state has taken to increase ERA uptake. The survey involved 502 participants, 94 percent of whom were female, and 98 percent of whom were housed. All survey respondents had a child under the age of nine. Figure 2 shows the racial and ethnic composition of survey respondents.

Findings

Census Pulse Data

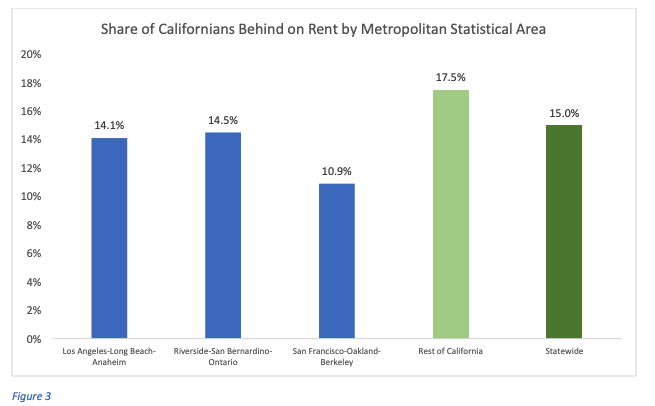

More than 1.8 million Californians are still behind on rent. According to the most recent Pulse data, 15 percent of adult Californian renters, representing over 1.8 million people are not caught up on rent. This is likely an underestimate, as many respondents may not be aware that their household has fallen behind on rent. Of those behind on rent nearly 18 percent, representing approximately 397,000 Californians, are three or more months behind.

The share of households that were behind on rent varied by region. Figure 3 shows how the major MSAs in California differed by the relative share of renter households in each that were not caught up on rent. On average, the regions that fell outside one of the three major MSAs areas observed by the Census had the highest share of tenants who were behind on their rent. The Bay Area (more specifically, the San Francisco-Oakland-Berkeley MSA) had the most tenants who reported being caught up on their rent.

ACCESS Study Survey

Few participants in the ACCESS Study received ERA. Among renters who responded to the ACCESS survey, 22 percent reported that since March 2020 they had deferred payment of rent. Almost the same share of renters in the ACCESS group—23 percent—had applied for ERA by the time the survey was conducted. Only 7 percent had in fact received ERA.

BHHI asked the 77 percent of respondents who had not sought rental assistance why they chose not to. A majority (51 percent) thought they did not need it; nearly one-third (29 percent) did not know the program existed.

The ACCESS Study was not intended to be representative, but instead to capture how a particular subset of the population—lower-income parents of young children—may be affected by public policy during the COVID-19 pandemic. We believe that the results, while not conclusive, are certainly suggestive.

Discussion

While the state’s actions have thus far managed to avert a major “eviction cliff,” the Census Pulse data indicate that a significant share of California renters are still in need of ERA if they are going to avoid being removed from their homes. This is particularly true in regions of the state that fall outside any of the three major MSAs observed by the Census Pulse Survey. Furthermore, the ACCESS survey results show how the risk of eviction is particularly concentrated among particular subpopulations.

One of the primary obstacles to ERA uptake appears to be lack of awareness on the part of renters— both of their eligibility status, and of the program itself. This suggests that simply making more renters aware of both the ERA program’s existence and their own potential eligibility status could help prevent significant disruption in their lives.

The need to make eligible renters aware of ERA and help them access the program has become especially pressing as the end of California’s eviction moratorium draws closer. While the state’s efforts to make sure that landlords cannot evict ERA-eligible tenants over unpaid rent are laudable, they are unlikely to protect everyone. Some tenants, unaware of the law, may vacate their apartments out of fear that they are about to be evicted. Others may receive a favorable judgment from the eviction courts, but only after destabilizing and potentially traumatic legal battles.

The optimal outcome for renters is not simply to avoid eviction, but to avoid even the risk of eviction. An extension of the statewide eviction moratorium would be the surest way to remove this risk. Unfortunately, a recent court decision which limited New York’s moratorium may make extending protections challenging in California.iii In lieu of a blanket moratorium, the best safeguard against eviction for those who are behind on rent is receipt of ERA before their landlord threatens them with eviction proceedings.

Recommendations

With the statewide eviction moratorium set to expire, public and nonprofit service providers should prioritize making as many low-income renters as possible aware of their potential eligibility for ERA. Furthermore, service providers should dedicate resources to assisting eligible renters with the ERA application process.

For example, the following actions could increase ERA awareness and accessibility among the eligible population:

- The California Department and Social Services (CDSS) could release guidance advising county welfare departments to provide their clients with information on ERA.

- Medi-Cal managed care plans could alert plan beneficiaries that they may be eligible for ERA.

- Non-profit service providers could share information about ERA and dedicate staff to assisting clients with the ERA application.

- School districts with a significant proportion of low-income students could alert parents that they may be eligible for ERA. (Some districts, such as Oakland Unified School District, are already doing this.)

- Local agencies and non-profits could partner with community organizations—such as local churches—to disseminate information about ERA and assist community members with filling out applications.

These efforts should be statewide but concentrated in areas where there is a particularly high share of tenants who are behind on their rent, as captured by the Census Pulse Survey.

Conclusion

While the distribution of ERA in California got off to a slow start, the state has made significant strides in accessibility and uptake. However, many ERA-eligible renters remain at risk; the upcoming end of the eviction moratorium has made delivering assistance to those households even more urgent. It is critical that the state continue to build on the progress it has already made.

Furthermore, the state should consider how the experience of ERA implementation can inform future assistance programs. Over the past year, the state has made numerous adjustments to program design and delivery, largely to address gaps in awareness and barriers to utilization. Lessons learned from this trial-and-error approach can be incorporated into the program design of other state initiatives.

Contact: Ned Resnikoff, UCSF BHHI Policy Manager | Arq.Erfavxbss@hpfs.rqhude.fscu@ffokinseR.deN

i Goldstein and Reina. “An Early Analysis of the California COVID-19 Rental Relief Program.” Housing Initiative at Penn. July 2021. https://www.housinginitiative.org/uploads/1/3/2/9/132946414/hip_carr_7.9_final.pdf

ii “California COVID-19 Rent Relief Program Dashboard.” California Department of Housing and Community Development. Accessed September 13, 2021. https://housing.ca.gov/covid_rr/dashboard.html

iii Howe, Amy. “Court partially blocks New York eviction moratorium.” SCOTUSblog. August 12, 2021. https://www.scotusblog.com/2021/08/court-partially-blocks-new-york-eviction-moratorium/