Every time I do a talk or a panel about housing and homelessness, I get some version of the following question: “Can’t we just house people in all those vacant apartments?”

The premise of the question is that while it may seem like California is suffering from a housing shortage, our high-cost metropolitan areas are in fact full of housing that nobody is using. Many of these homes and apartments are being held as investment properties by various nefarious actors—predatory financial institutions, money-laundering oligarchs, etc.—who, in some versions of the theory, are keeping them vacant as part of a deliberate strategy to induce artificial scarcity and inflate housing costs.

Proponents of this theory note that rental vacancies (as measured by the United States Census Bureau) exceed the number of homeless people (as measured by Department of Housing and Urban Development’s annual Point-in-Time count) in many cities. For example, in 2018 the Census Bureau counted approximately 34,000 vacant units in San Francisco; a citywide 2019 Point-in-Time count found closer to 8,000 homeless people. That means there are close to four empty homes for every one unhoused San Franciscan!

It’s a nice story. The numbers lend it some plausibility, it offers us an easily identifiable villain, and—most importantly—it offers us a convenient escape from the present homelessness crisis. Maybe we don’t need to build any additional housing, the story tells us. Maybe we don’t have to choose between ending homelessness and keeping our neighborhoods exactly the way they are. All we need to do is slot people into the housing that is already available.

Like I said, it’s a nice story. Unfortunately, it isn’t true.

Unfudging the Numbers

The above theory—which, by way of shorthand, I’ll call the artificial scarcity theory of homelessness—is based on a misuse of the underlying data. Here is how the Census Bureau defines a vacant housing unit for the purpose of calculating its vacancy rate (emphasis mine):

A housing unit is vacant if no one is living in it at the time of the interview, unless its occupants are only temporarily absent. In addition, a vacant unit may be one which is entirely occupied by persons who have a usual residence elsewhere. New units not yet occupied are classified as vacant housing units if construction has reached a point where all exterior windows and doors are installed and final usable floors are in place. Vacant units are excluded if they are exposed to the elements, that is, if the roof, walls, windows, or doors no longer protect the interior from the elements, or if there is positive evidence (such as a sign on the house or block) that the unit is to be demolished or is condemned. Also excluded are quarters being used entirely for nonresidential purposes, such as a store or an office, or quarters used for the storage of business supplies or inventory, machinery, or agricultural products. Vacant sleeping rooms in lodging houses, transient accommodations, barracks, and other quarters not defined as housing units are not included in the statistics in this report.

The Census Bureau’s data makes no distinction between long-term and short-term vacancies. A unit that is unoccupied for a period of one or two weeks counts the same as a unit that is being held perpetually empty. In fact, the above definition explicitly includes newly built units for which the developer or property manager have not yet found an occupant. As soon as the windows, doors and floors are in place, a house transitions from being under construction to “vacant.”

We simply don’t know how many of the units in the Census count are being held vacant over the long term as investment properties. But it is worth noting that most homes and apartments go through a short period of vacancy between when they are built and when they become occupied; similarly, when a tenant moves out of an apartment, we can usually expect a brief gap in occupancy before the next tenant signs a lease. We can therefore surmise that routine, short-term vacancies represent a significant share of the overall vacancy rate. San Francisco almost certainly does not have 34,000 permanently empty units of housing just sitting around.

Furthermore, while the artificial scarcity theory significantly overstates California’s long-term vacancy rate, it also understates the scale of homelessness. That’s because the Point-in-Time count does not actually tell us how many people are homeless in a given city. Instead, as the Department of Housing and Urban Development says on its official site, the Point-in-Time count “is a count of sheltered and unsheltered people experiencing homelessness on a single night in January.” (Emphasis mine.)

In other words, anyone who is homeless on any other night of the year—but not that one particular night—is not included in the count. Given that most people in the homeless population are not chronically homeless, that means the Point-in-Time count probably leaves out a lot of people. If we were to count the number of San Franciscans who were homeless at any point in 2019, we would probably end up with a number significantly higher than 8,000. (Furthermore, the point-in-time count is an undercount on even its own terms. Because it tracks only visibly sheltered and unsheltered people, it can miss individuals who are out of sight or in places other than shelters, such as hospitals and jails.)

What the Vacancy Rate Really Tells Us

Despite their limitations, both the Point-in-Time count and the Census Bureau’s vacancy rate are still useful. By comparing year-over-year Point-in-Time estimates, we can get a pretty good sense of whether the rate of homelessness is growing or shrinking. Similarly, we can learn a lot by looking at trends in city vacancy rates, or by comparing vacancy rates across cities.

Let’s try a thought experiment. Imagine that the artificial scarcity theory of homelessness is correct: wealthy investors are gobbling up units in high-cost metros and leaving them vacant, thereby pushing costs even higher and forcing more people into homelessness. In other words, vacancies are driving homelessness; as a city’s vacancy rate increases, we would expect its homelessness rate to increase in tandem.

On the other hand, we would expect to see the opposite relationship if the artificial scarcity theory is wrong. Under that scenario, housing costs should be highest where the vacancy rate is lowest, because fewer vacancies indicate a lower supply of housing relative to demand. So a low vacancy rate becomes a proxy for high housing costs, and we find homelessness to be most extreme where there are the fewest empty units.

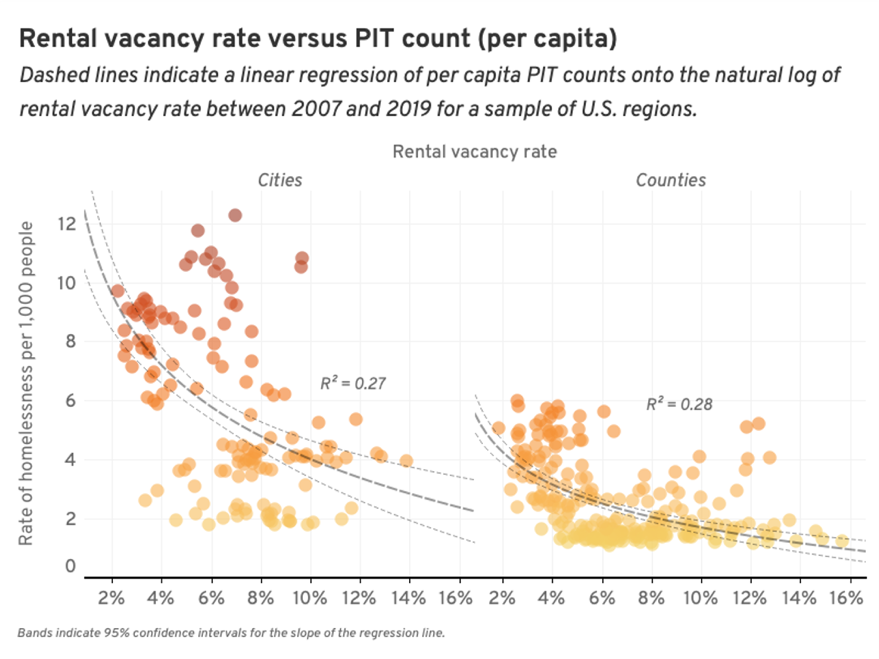

We can test which of the above theories is correct by comparing city Point-in-Time counts to vacancy rates. Lucky for us, some researchers have already done exactly that. The following chart is from an upcoming book by Gregg Colburn and Clayton Aldern called, appropriately enough, Homelessness is a Housing Problem:

What we see in this chart is the exact opposite of what the artificial scarcity theory tells us should be happening: the homelessness rate appears to be highest in the cities where rental vacancy rates are lowest. The second story—that high-cost cities like San Francisco have unusually low vacancy rates for the same reason that so many of their residents are homeless—is the correct one.

No Shortcuts

I understand the appeal of the artificial scarcity theory. While I don’t share the principled objections of many of its proponents to more housing development, there is no question that it would be nice to live in a world where we could solve homelessness without it. Building takes time and costs a lot of money, although there are ways the state could make it faster and cheaper. Furthermore, there is tremendous opposition to building more housing in the places that most need it, including (often especially) building more extremely affordable housing. If only we could end the homelessness crisis quickly, cheaply, and without grueling wars of political attrition.

The artificial scarcity theory promises a nice little workaround. It tells us that we already have all the housing capacity we need, and that we just need to make better use of it. In other words, it promises a shortcut.

Unfortunately, that shortcut is illusory. There are no shortcuts out of a genuine crisis, especially one that has been allowed to fester unchecked for decades. And we cannot adequately address a crisis unless we face up to the full magnitude of what that will demand. We cannot end the homelessness crisis without building more extremely low-income housing—and more housing in general.