Abstract

Background

In the US, the median age of adults experiencing homelessness and incarceration is increasing. Little is known about risk factors for incarceration among older adults experiencing homelessness. To develop targeted interventions, there is a need to understand their risk factors for incarceration.

Objective

To examine the prevalence and risk factors associated with incarceration in a cohort of older adults experiencing homelessness.

Design

Prospective, longitudinal cohort study with interviews every 6 months for a median of 5.8 years.

Participants

We recruited adults ≥50 years old and homeless at baseline (n=433) via population-based sampling.

Main Measures

Our dependent variable was incident incarceration, defined as one night in jail or prison per 6-month follow-up period after study enrollment. Independent variables included socioeconomic status, social, health, housing, and prior criminal justice involvement.

Key Results

Participants had a median age of 58 years and were predominantly men (75%) and Black (80%). Seventy percent had at least one chronic medical condition, 12% reported heavy drinking, and 38% endorsed moderate-severe use of cocaine, 8% of amphetamines, and 7% of opioids. At baseline, 84% reported a lifetime history of jail stays; 37% reported prior prison stays. During follow-up, 23% spent time in jail or prison. In multivariable models, factors associated with a higher risk of incarceration included the following: having 6 or more confidants (HR=2.13, 95% CI=1.2–3.7, p=0.007), remaining homeless (HR=1.72, 95% CI=1.1–2.8, p=0.02), heavy drinking (HR=2.05, 95% CI=1.4–3.0, p<0.001), moderate-severe amphetamine use (HR=1.89, 95% CI=1.2–3.0, p=0.006), and being on probation (HR=3.61, 95% CI=2.4–5.4, p<0.001) or parole (HR=3.02, 95% CI=1.5–5.9, p=0.001).

Conclusions

Older adults experiencing homelessness have a high risk of incarceration. There is a need for targeted interventions addressing substance use, homelessness, and reforming parole and probation in order to abate the high ongoing risk of incarceration among older adults experiencing homelessness.

Similar content being viewed by others

INTRODUCTION

Individuals experiencing homeless in the United States (US) have high lifetime rates of incarceration, with estimates ranging from 20 to 70%.1,2,3,4,5,6 Homelessness and incarceration share many risk factors, both health-related (i.e., substance use and mental health problems)3,6,7,8,9,10,11,12 and economic (i.e., lower education and unemployment).9,13 Individuals experiencing homelessness have an increased risk of police citations related to survival behaviors (e.g., sleeping in public, panhandling), heightened visibility to law enforcement, and decreased ability to adhere to conditions of parole or pay citations, increasing the risk of arrest.14,15,16 There is a bidirectional relationship between homelessness and incarceration. After incarceration, people have an increased rate of homelessness,16,17,18 and incarceration leads to increased housing vulnerability due to loss of housing during incarceration, decreased eligibility for employment and public housing, and disrupted community ties.16,17,18

The average age of single adults experiencing homelessness in the US has increased; the proportion age 50 or older is growing.19 The US criminal justice population is also aging.20,21,22,23 Adults 55 or older in prison increased by 366% between 1999 and 2016,24 and in jails, by 278% between 1996 and 2008.21 The prevalence of, and risk factors for, incarceration among older adults experiencing homelessness remains unexamined.

Most studies examining incarceration and housing instability are retrospective or cross-sectional analyses including all ages.1,2,3,4 In the general population, incarceration decreases with age, though rates remain high among older homeless adults. Understanding older adults’ unique risk factors for incarceration is critical to target interventions to prevent criminal justice involvement. This is increasingly important as the COVID-19 pandemic has had a disproportionate impact on people living in congregate settings.25,26,27,28 Understanding movement between homelessness and the criminal justice system can inform interventions to prevent SARS COV-2 transmission, particularly among older adults who are at increased risk of severe disease and death.25,26,29,30,31 Therefore, in a prospective cohort of older adults who were homeless at study entry, we examined factors associated with subsequent incarceration over the multi-year study period including sociodemographic, social, housing, and health factors. We hypothesized that continued homelessness, substance use, mental illness, and cognitive impairment would be associated with incident incarceration.

METHODS

Study Overview

The Health Outcomes in People Experiencing Homelessness in Older Middle agE (HOPE HOME) study is a prospective cohort study of health and life course events among older adults experiencing homelessness.32 The University of California, San Francisco Institutional Review Board approved this study.

Sample and Recruitment

We used population-based sampling to recruit 350 individuals age 50 and older experiencing homelessness in Oakland, CA, from July 2013 to June 2014 (HOPE HOME 1).32,33,34 Between August 2017 and July 2018, we recruited an additional 100 participants, age 53 and older (HOPE HOME 2). Research staff administered interviews and conducted clinical assessments at baseline and every 6 months. In this study, we excluded participants who died before the first follow-up interview, withdrew from the study, or did not provide their full name, which precluded queries of correctional records. We censored participants at time of death. We ceased this analysis in February 2020.

Study Design and Population

Eligibility criteria included the following: (1) currently homeless as defined by the Homeless Emergency Assistance and Rapid Transitions to Housing (HEARTH) Act,35 (2) age 50 or 53 and older for HOPE HOME 1 and HOPE HOME 2 respectively, (3) English-speaking, and (4) ability to give informed consent.36 Participants received $25 for enrollment interviews, $5 for monthly check-ins, and $15 for 6-month follow-up interviews.

MEASURES

Incarceration

Our primary outcome was incarceration, defined as having spent at least one night in jail or prison (state or federal) in each follow-up period. At baseline, we asked participants about their incarceration history. At each 6-month visit, we asked whether they spent any nights in jail or prison in the last 6 months, and if they were on parole or probation. If participants missed visits, we examined the local jail records and State and Federal prison records to determine if they were in custody. If we heard from a participant’s contacts that they were in jail or prison, we queried those records.

Independent Variables

Sociodemographic Characteristics

We assessed age, gender, and race/ethnicity. Participants reported their highest educational attainment and whether they served in the US military.

Participants reported how much they had worked in the past 30 days, dichotomized as ≥20 h per week versus less. Participants reported their income in the past 30 days; we categorized as formal (i.e., income from jobs or government programs) or informal (i.e., money from friends or family, income from selling things, or panhandling).37 We asked about illicit income including selling drugs or sex.

Social Support

We used a validated measure of social support defined as the number of people in whom the participant felt they could confide (0, 1–5, or ≥6).38,39 To assess community support, we asked participants if they attended a place of worship, community center, or social meeting regularly.

Homelessness

We asked participants about duration of homelessness and at what age they had first experienced homelessness, dichotomized as first becoming homeless at ≥50 years old versus younger. We calculated duration of homelessness in adulthood based on duration of homelessness in three age ranges: 18–25, 26–49, and ≥50 years.

All participants met HEARTH criteria at baseline. Participants remained in the study regardless of whether they continued to meet HEARTH criteria. To assess continued homelessness, we examined whether participants met HEARTH criteria at each visit. To assess unsheltered homelessness, we asked participants to report each place they had stayed during the prior 6 months.40 We defined an unsheltered night as sleeping any place not meant for human habitation. We categorized participants as having spent any versus no unsheltered nights in the prior 6 months.41

Health History

We assessed self-reported health (fair or poor versus good, very good, or excellent).42 Participants reported if they had chronic conditions including hypertension, coronary artery disease or myocardial infarction, congestive heart failure, stroke, diabetes, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease or asthma, arthritis, cancer, or HIV/AIDS.37

To assess functional impairment, we asked participants about their ability to complete activities of daily living (ADLs): bathing, transferring, toileting, dressing, or eating.43 To evaluate global cognitive impairment, we used the Modified Mini-Mental State Examination (3MS), and for executive function, the Trails B assessment, at the baseline visit. For 3MS and Trails B, we considered those who scored below the 7th percentile (1.5 standard deviations below a reference cohort mean) or were unable to complete the assessment (defined as taking ≥5 min) as impaired.44,45 We assessed self-reported hospitalization in the past 6 months.7

Mental Health and Substance Use

To assess mental health problems we used questions from the National Survey of Homeless Assistance Providers and Clients (NSHAPC), as adapted from the Addiction Severity Index (ASI).46,47

To assess heavy drinking, we considered those who reported having ≥6 alcoholic drinks on one occasion at least monthly as heavy drinking.48 To assess drug use (cocaine, amphetamines, cannabis, and opioids) in the last 6 months, we used the World Health Organization’s (WHO) Alcohol, Smoking, and Substance Involvement Screening Test (ASSIST), a score of ≥4 indicated moderate-to-severe use.49

Victimization

We asked participants if they had experienced verbal, physical, or sexual assault before age 18. We asked about physical or sexual assault in the prior 6 months.50

Statistical Analysis

We completed a descriptive analysis using all variables from baseline. Variables included only in the descriptive analysis were income, illicit income sources, duration of homelessness, hospitalizations, and history of incarceration. To identify risk factors for incarceration, we selected independent variables based on our hypotheses. We assessed bivariable associations between a priori independent variables and incarceration using an extended Cox hazard model to incorporate multiple, independent events and time-varying covariates. We used 6-month intervals as the period of measure for time-to-event outcomes. In the hazard models, we included demographics (i.e., gender, race), life history (i.e., education, veteran status, age first homeless, victimization prior to age 18), and cognitive impairment (i.e., 3MS and Trails B) as time-constant variables assessed at baseline. We included all other variables as time-varying.

We estimated our multivariable model by including variables with bivariable type III p-values < 0.20. If a categorical variable had more than two levels, we included all levels in our multivariable model if any type III p-value was < 0.20. We reduced the model using backward elimination by retaining variables with type III p-values < 0.05 in our final model. We conducted our analysis in SAS using complete case analysis and robust confidence intervals. In a sensitivity analysis, we estimated models without the probation and parole variables.

We estimated models separately for homelessness based on HEARTH and nights unsheltered to assess the role of unsheltered homelessness and rehousing on incarceration. First, we estimated models including HEARTH and covariates. Then, we replaced HEARTH with any nights unsheltered.

RESULTS

Study Sample

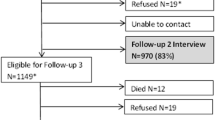

We enrolled 350 participants in HOPE HOME 1 and 100 in HOPE HOME 2 and followed them for a median of 5.8 years (IQR 2.4–6.2 years) (Fig. 1). We excluded individuals who died before the first follow-up visit (n=15), for whom we could not validate correctional records (n=1), or who withdrew (n=1).

Participant Characteristics at Baseline

Among the 433 participants, the median age was 58 (IQR 53, 63) at baseline (Table 1). Seventy-five percent were male, 80% were Black, 22% were US Veterans, and 74% had completed high school or a GED program. Four percent were employed ≥20 h a week with an average monthly income of $705; 40% reported informal income sources. Less than 1% reported illicit income (n=4).

Approximately half (52%) endorsed community support and 68% reported at least one confidant. On average, participants had been homeless for 6.9 years and 44% became homeless after age 50; 82% had spent a night unsheltered in the 6 months prior to the study.

Dependent Variable: Incident Incarceration

During follow-up, 98 participants (23%) spent time in jail or prison. Of those 98 participants, 57% had only one incarceration event (Fig. 2).

Health History

Forty-five percent rated their health as fair or poor, 70% had at least one chronic medical condition, and 39% reported difficulty with at least one ADL. Eighteen percent were hospitalized within 6 months of enrollment. Eighteen percent had cognitive impairment based on 3MS and 12% had executive dysfunction based on Trails B.

Mental Health and Substance Use

Over half reported depressive symptoms (67%) and hallucinations (61%); 75% reported severe anxiety. Over half (58%) reported ever taking a psychiatric medication, 27% had a lifetime history of suicidal ideation, and 21% reported ever being hospitalized for a mental health condition. Twelve percent of participants reported heavy drinking. Approximately half met criteria for moderate-to-severe cannabis use (49%); over one-third (38%) for cocaine, and less than 10% for amphetamines (8%), or opioids (7%). Over half (58%) reported victimization prior to age 18; 11% reported physical or sexual assault within the preceding 6 months.

Lifetime Criminal Justice Involvement

Eighty-four percent reported prior incarceration in jail and 37% in prison. At baseline, 14% were on probation and 3% were on parole.

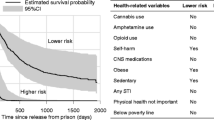

Factors Associated with Incarceration

In multivariable analysis (Table 2), factors associated with having an incarceration event included having 6 or more confidants (versus none) (HR 2.13, 95% CI 1.2–3.7, p=0.007), remaining homeless per HEARTH criteria (HR 1.72, 95% CI 1.1–2.8, p=0.02), heavy drinking (HR 2.05, 95% CI 1.4–3.0, p<0.001), moderate-severe amphetamine use (HR 1.89, 95% CI 1.2–3.0, p=0.006), and probation (HR 3.61, 95% CI 2.4–5.4, p<0.001), or parole (HR 3.02, 95% CI 1.5–5.9, p=0.001). Factors that were borderline significant included age (HR 0.97, 95% 0.9–1.0, p=0.06), male gender (HR 1.67, 95% 1.0–2.9, p=0.07), and having 1–5 (versus 0) confidants (HR 1.55, 95% 1.0–2.4, p=0.05).

Informal income sources, mental health hospitalizations, recent physical or sexual assault, and moderate-severe opioid or cocaine use were associated with incarceration in bivariable but not multivariable analyses.

Sensitivity Analysis

In a sensitivity analysis, we found that removing parole or probation status from the model made our borderline significant variables including age (HR 0.95, 95% CI 0.9–1.0, p=0.02), male gender (HR 2.15, 95% CI 1.2–3.9, p=0.01), and 1–5 confidants (HR 1.72, 95% CI 1.1–2.7, p=0.02) become statistically significant; otherwise, it did not significantly change our results. To examine whether the increased risk of homelessness is from unsheltered homelessness, we replaced continued homelessness (by HEARTH) with unsheltered homelessness. We found that unsheltered homelessness (compared to sheltered homelessness or housing) had a similar hazard ratio to homelessness overall (HR 1.73, 95% CI 1.2–2.6, p=0.007). Replacing homelessness with unsheltered homelessness did not change other variables. There were no significant changes in other variables.

The 17 participants whom we excluded from analysis were 4 years older and had a higher rate of hospital admissions (53% versus 18%) at baseline; there were no other significant differences.

DISCUSSION

In this prospective study of older adults experiencing homelessness, almost one-quarter experienced at least one incarceration event during follow-up. We found several risk factors for incarceration that are associated in the general adult population, including substance use, and being on parole or probation. Building on prior data about the association between homelessness and incarceration, we found that individuals who continued to experience homelessness at follow-up had an elevated risk of incarceration compared to those who exited homelessness. We found that having a larger social network is associated with incarceration, which has not been reported previously.

Though the median age of the cohort at baseline was 58, participants had a burden of disease and disability commensurate with adults aged 15–20 years older.51,52 Individuals experiencing homelessness, like those in prisons, experience an early onset of geriatric conditions and are considered “older” by age 50.52,53 Despite this population’s relative frailty, study participants continued to experience incarceration. Incarceration presents health risks, particularly for older adults; these threats have intensified during the COVID-19 pandemic.54

Housing status was dynamic and approximately half exited homelessness during study follow-up;32 remaining homeless was independently associated with risk of incident incarceration. Homelessness can increase the risk for incarceration via increased visibility to law enforcement, via increased illicit economic behaviors (e.g., shoplifting), via participation in criminalized survival behaviors (e.g., sleeping or urinating in public) or via barriers to completing court-mandated interventions (e.g., inability to keep ankle monitor charged). The direction of the association may be reversed; it is possible that individuals who experienced incarceration may have faced additional barriers to accessing housing, prolonging homelessness.

Substance use was common and increased the risk of incarceration. Alcohol and amphetamine intoxication can lead to impulsive behavior and impaired judgment, which may increase illegal activity or visibility to law enforcement. For individuals on parole or probation, substance use may be monitored and any use may result in time in jail or prison. Our prior research showed that only one-in-eight older individuals experiencing homelessness with need for substance use treatment received such treatment, highlighting an unmet need.55

Counter to our hypothesis, social support was not associated with decreased risk of incarceration, instead a higher number of confidants was associated with a higher risk. Those with larger social networks may have more peers who are involved in the criminal justice system, increasing the risk of incarceration.56 There is a need to understand the nature of social support that is associated with an increased risk of arrest in order to interrupt this cycle, either by encouraging social networks with positive outcomes or by disrupting cycles of arrests.

In this study, Black race was not associated with incarceration, although it is well established that Black Americans are disproportionately incarcerated due to structural racism.57,58,59 Black Americans are significantly more likely to become homeless due to structural racism (i.e., educational and employment discrimination, lack of family wealth and homeownership) so there may be lower rates of individual risk factors for incarceration (e.g., behavioral health challenges).60 Thus, non-Black participants may have individual risk factors that elevated their risk of incarceration in a way that we did not account for. Future studies should be conducted to better understand this finding.

As continued homelessness is associated with incarceration, it is possible that rehousing older adults experiencing homelessness could reduce this risk. A recent randomized controlled trial of permanent supportive housing for chronically homeless adults did not find a reduction in jail use. This may have been explained by police having an increased ability to serve outstanding warrants to people upon rehousing.61 Given the high rates of substance use, expansion of substance use treatment programs might reduce older homeless adults’ risk of incarceration. Among all variables that we tested, parole and probation (community supervision) had the highest hazard ratio. Recidivism may be driven by technical violations of probation or parole (e.g., failure to complete court-mandated testing or follow-up, use of prohibited substances) rather than new criminal offenses. There are movements to reform probation and parole because they may perpetuate incarceration.62,63 Reform efforts include shortening supervision sentences, reducing conditions and cost, limiting incarceration for violations, and providing specialty community supervision programs which use probation officers with health-focused expertise who incorporate a treatment-oriented approach in collaboration with community resources.64 Future areas for research include whether reducing or tailoring supervision programs to the needs and risk factors of older homeless adults decreases recidivism. Another innovation is specialty courts (i.e., drug and mental health courts), which emphasize connection to treatment, though there is mixed data on their impact on incarceration and recidivism.65

Limitations

It is possible that we undercounted incarceration events because we relied on participant self-report and manual review of custodial records; participants may have underreported visits, or jail and prison stays may have occurred outside the window in which we checked, or outside of the correctional facilities that we were able to monitor. Such undercounting could have made it more difficult for us to find associations. Participants who spent longer times in custody were less likely to experience multiple incarcerations; we did not control for length of incarceration. We did not have detailed data on incarceration events, including the cause of arrest, duration of incarceration, or whether the participants were charged or prosecuted.

CONCLUSIONS

Older adults who experience homelessness have a high prevalence of lifetime incarceration and elevated incidence of incarceration even during older age. This is related to a combination of individual (i.e., larger social network, alcohol or amphetamine use) and structural risk factors (i.e., continued homelessness, parole or probation). Future research is needed to examine whether targeted interventions for older adults experiencing homelessness, including substance use treatment, housing access, and geriatrics-focused community supervision programs, prevent criminal justice involvement in this rapidly growing population.

References

McGuire JF, Rosenheck RA. Criminal History as a Prognostic Indicator in the Treatment of Homeless People With Severe Mental Illness. Psychiatr Serv. 2004;55(1):42-48.

Kushel MB, Hahn JA, Evans JL, Bangsberg DR, Moss AR. Revolving Doors: Imprisonment Among the Homeless and Marginally Housed Population. Am J Public Health. 2005;95(10):1747-1752.

Tsai J, Rosenheck RA. Incarceration Among Chronically Homeless Adults: Clinical Correlates and Outcomes. J Forensic Psychol Pract. 2012;12(4):307-324.

Metraux S, Culhane DP. Recent Incarceration History Among a Sheltered Homeless Population. Crime Delinq. 2006;52(3):504-517.

Roy L, Crocker AG, Nicholls TL, Latimer EA, Ayllon AR. Criminal Behavior and Victimization Among Homeless Individuals With Severe Mental Illness: A Systematic Review. Psychiatr Serv. 2014;65(6):739-750.

Weiser SD, Neilands TB, Comfort ML, et al. Gender-Specific Correlates of Incarceration Among Marginally Housed Individuals in San Francisco. Am J Public Health. 2009;99(8):1459-1463.

McNiel DE, Binder RL, Robinson JC. Incarceration Associated With Homelessness, Mental Disorder, and Co-occurring Substance Abuse. Psychiatr Serv. 2005;56(7):840-846.

Ann Elizabeth M, Dorota S, Jessica M, Paul H, Dennis PC. Homelessness, Unsheltered Status, and Risk Factors for Mortality. Publ Health Rep. (1974-). 2016;131(6):765-772.

Greenberg GA, Rosenheck RA. Homelessness in the state and federal prison population. Crim Behav Ment Health. 2008;18(2):88-103.

Walsh C, Hubley AM, To MJ, et al. The effect of forensic events on health status and housing stability among homeless and vulnerably housed individuals: A cohort study. PLoS One 2019;14(2):e0211704.

Lambdin BH, Comfort M, Kral AH, Lorvick J. Accumulation of Jail Incarceration and Hardship, Health Status, and Unmet Health Care Need Among Women Who Use Drugs. Womens Health Issues. 2018;28(5):470-475.

Greenberg GA, Rosenheck RA. Jail incarceration, homelessness, and mental health: a national study. Psychiatr Serv. 2008;59(2):170-177.

Nilsson S, Nordentoft M, Hjorthøj C. Individual-Level Predictors for Becoming Homeless and Exiting Homelessness: a Systematic Review and Meta-analysis. J Urban Health. 2019;96(5):741-750.

Mitchell J, Clark C, Guenther C. The Impact of Criminal Justice Involvement and Housing Outcomes Among Homeless Persons with Co-occurring Disorders. Community Ment Health J. 2017;53(8):901-904.

Bill M, John H. HOMELESSNESS: A CRIMINOGENIC SITUATION? Bri J Criminol. 1991;31(4):393-410.

Couloute L. Nowhere to Go: Homelessness among formerly incarcerated people. In. Prison Policy Initiative; 2018.

Herbert CW, Morenoff JD, Harding DJ. Homelessness and Housing Insecurity Among Former Prisoners. 2015.

To MJ, Palepu A, Matheson FI, et al. The effect of incarceration on housing stability among homeless and vulnerably housed individuals in three Canadian cities: A prospective cohort study. Can J Public Health. 2017;107(6):e550-e555.

Culhane DP, Metraux S, Byrne T, Stino M, Bainbridge J. The Age Structure of Contemporary Homelessness: Evidence and Implications For Public Policy. Anal Soc Issues Public Policy. 2013;13(1):228-244.

Carson EA, Sabol WJ. Aging of the State Prison Population, 1993-2003<br>. Spec Rep. 2016.

Greene M, Ahalt C, Stijacic-Cenzer I, Metzger L, Williams B. Older adults in jail: high rates and early onset of geriatric conditions. Health Justice. 2018;6(1):1-9.

Chodos AH, Ahalt C, Cenzer IS, Myers J, Goldenson J, Williams BA. Older Jail Inmates and Community Acute Care Use. Am J Public Health. 2014;104(9):1728-1733.

Office of the Inspector G. The Impact of an Aging Inmate Population on the Federal Bureau of Prisons. 2016.

McKillop M, Boucher A. Aging Prison Populations Drive Up Costs. 2018.

Barnert E, Ahalt C, Williams B. Prisons: Amplifiers of the COVID-19 Pandemic Hiding in Plain Sight. Am J Public Health. 2020;110(7):964-966.

Nelson B, Kaminsky DB. A COVID-19 crisis in US jails and prisons. Cancer Cytopathol. 2020;128(8):513-514.

Albon D, Soper M, Haro A. Potential Implications of the COVID-19 Pandemic on the Homeless Population. Chest. 2020;158(2):477-478.

Kuehn BM. Homeless Shelters Face High COVID-19 Risks. JAMA. 2020;323(22):2240-2240.

Franco-Paredes C, Jankousky K, Schultz J, et al. COVID-19 in jails and prisons: A neglected infection in a marginalized population. PLoS Negl Trop Dis. 2020;14(6):e0008409.

Puglisi LB, Malloy GSP, Harvey TD, Brandeau ML, Wang EA. Estimation of COVID-19 Basic Reproduction Ratio in a Large Urban Jail in the United States. Ann Epidemiol. 2020.

Saloner B, Parish K, Ward JA, DiLaura G, Dolovich S. COVID-19 Cases and Deaths in Federal and State Prisons. JAMA. 2020;324(6):602-603.

Lee CT, Guzman D, Ponath C, Tieu L, Riley E, Kushel M. Residential patterns in older homeless adults: Results of a cluster analysis. Soc Sci Med. (1982). 2016;153:131-140.

Burnam MA, Koegel P. Methodology for Obtaining a Representative Sample of Homeless Persons:The Los Angeles Skid Row Study. Eval Rev 1988;12(2):117-152.

Henry M, Watt R, Rosenthal L, Shivji A. The 2017 Annual Homeless Assessment Report (AHAR) to Congress. Washington: DC: The U.S. Department of Housing and Urban Development: Office of Community Planning and Development; 2017.

Homeless Emergency Assistance and Rapid Transition to Housing Act of 2009. Definition of homelessness., P.L. 111-22, Sec. 1003. 2009.

Dunn LB, Jeste DV. Enhancing informed consent for research and treatment. Neuropsychopharmacology. 2001;24(6):595-607.

National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey: questionnaires, datasets, and related documentation. Atlanta, GA: Centers for Disease Control and Prevention; 2009.

Gielen AC, O’Campo PJ, Faden RR, Kass NE, Xue X. Interpersonal conflict and physical violence during the childbearing year. Soc Sci Med 1994;39(6):781-787.

Riley ED, Cohen J, Knight KR, Decker A, Marson K, Shumway M. Recent violence in a community-based sample of homeless and unstably housed women with high levels of psychiatric comorbidity. Am J Public Health 2014;104(9):1657-1663.

Tsemberis S, McHugo G, Williams V, Hanrahan P, Stefancic A. Measuring homelessness and residential stability: The residential time-line follow-back inventory. J Commun Psychol. 2006;35(1):29-42.

Tong MS, Kaplan LM, Guzman D, Ponath C, Kushel MB. Persistent Homelessness and Violent Victimization Among Older Adults in the HOPE HOME Study. J Interpers Violence. 2019;886260519850532.

Ware Jr JE, Kosinski M, Keller SD. A 12-Item Short-Form Health Survey: construction of scales and preliminary tests of reliability and validity. Med Care. 1996:220-233.

Katz S. Assessing self-maintenance: activities of daily living, mobility, and instrumental activities of daily living. J Am Geriatr Soc. 1983.

Bland RC, Newman SC. Mild dementia or cognitive impairment: the Modified Mini-Mental State examination (3MS) as a screen for dementia. Can J Psychiatry. 2001;46(6):506-510.

Reitan RM. Validity of the Trail Making Test as an Indicator of Organic Brain Damage. Percept Mot Skills. 1958;8(3):271-276.

Burt M, Aran L, Douglas T, Valente J, Lee E, Iwen B. Homelessness: Programs and the People they Serve: Findings from the National Survey of Homeless Assistance Providers and Clients, Technical Report. Washington, DC: The Urban Institute; 1999.

McLellan AT, Kushner H, Metzger D, et al. The Fifth Edition of the Addiction Severity Index. J Subst Abus Treat. 1992;9(3):199-213.

Babor TF, Higgins-Biddle JC, Saunders JB, Monteiro MG. The Alcohol Use Disorders Identification Test: Guidelines for Use in Primary Care. World Health Organization; 2001.

Humeniuk R, Henry-Edwards S, Ali R, Poznyak V, Monteiro M. The Alcohol, Smoking and Substance Involvement Screening Test (ASSIST): Manual for use in primary care. Geneva: World Health Organization;2010.

Straus MA, Hamby SL, Boney-McCoy SUE, Sugarman DB. The Revised Conflict Tactics Scales (CTS2): Development and Preliminary Psychometric Data. J Fam Issues. 1996;17(3):283-316.

Brown RT, Kiely DK, Bharel M, Mitchell SL. Geriatric syndromes in older homeless adults. J Gen Intern Med. 2012;27(1):16-22.

Gelberg L, Linn LS, Mayer-Oakes SA. Differences in health status between older and younger homeless adults. J Am Geriatr Soc. 1990;38(11):1220-1229.

Cohen CI. Aging and homelessness. Gerontologist. 1999;39(1):5-14.

Prost SG, Novisky MA, Rorvig L, Zaller N, Williams B. Prisons and COVID-19: A Desperate Call for Gerontological Expertise in Correctional Healthcare. Gerontologist. 2020.

Kaplan LM, Vella L, Cabral E, et al. Unmet mental health and substance use treatment needs among older homeless adults: Results from the HOPE HOME Study. J Commun Psychol. 2019;47(8):1893-1908.

Fergusson DM, Swain-Campbell NR, Horwood LJ. Deviant peer affiliations, crime and substance use: a fixed effects regression analysis. J Abnorm Child Psychol. 2002;30(4):419-430.

Ram Subramanian KR, Mai C. Divided Justice: Trends in Black and White Jail Incarceration, 1990-2013. New York: Vera Institute of Justice; 2018.

Nellis A. The Color of Justice: Racial and Ethnic Disparity in State Prisons. Washington DC: The Sentencing Project; 2016.

Project TS. Report to the United Nations on Racial Disparities in the U.S. Criminal Justice System: Regarding Racial Disparities in the United States Criminal Justice System. 2018.

Paul DW, Knight KR, Olsen P, Weeks J, Yen IH, Kushel MB. Racial discrimination in the life course of older adults experiencing homelessness: results from the HOPE HOME study. J Soc Distress Homeless 2020;29(2):184-193.

Raven MC, Niedzwiecki MJ, Kushel M. A randomized trial of permanent supportive housing for chronically homeless persons with high use of publicly funded services. Health Serv Res 2020;55(S2):797-806.

Horowitz JV, T. States can shorten probation and protect public safety. The Pew Charitable Trusts; 2020.

Human Rights Watch A. Revoked: How Probation and Parole Feed Mass Incarceration in the United States. 2020.

Skeem JL, Manchak S, Montoya L. Comparing Public Safety Outcomes for Traditional Probation vs Specialty Mental Health Probation. JAMA Psychiatr. 2017;74(9):942-948.

Dolce BL. Drug Courts Are Not the Answer: Toward a Health-Centered Approach to Drug Use. Drug Policy Alliance; 2011.

Acknowledgements

We gratefully acknowledge our colleagues Pamela Olsen, Stacy Castellanos, John Weeks, Steve King, Cheyenne Garcia, and Celeste Enriquez for their invaluable contributions to the HOPE HOME study. The authors also thank the staff at St. Mary’s Center, Allen Temple, and Lifelong Medical Care and the HOPE HOME Community Advisory Board for their guidance and partnership.

Funding

The authors receive funding from the National Institute of Health (R01AG041860, K24AG046372, R24AG065175).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of Interest

The authors declare that they do not have a conflict of interest.

Disclaimer

These funding sources had no role in the preparation, review, or approval of the manuscript

Additional information

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Prior Presentations

This study was accepted for an oral abstract at the 2020 Society of General Internal Medicine Annual Meeting which was cancelled due to the COVID-19 pandemic.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Garcia-Grossman, I., Kaplan, L., Valle, K. et al. Factors Associated with Incarceration in Older Adults Experiencing Homelessness: Results from the HOPE HOME Study. J GEN INTERN MED 37, 1088–1096 (2022). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11606-021-06897-0

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s11606-021-06897-0